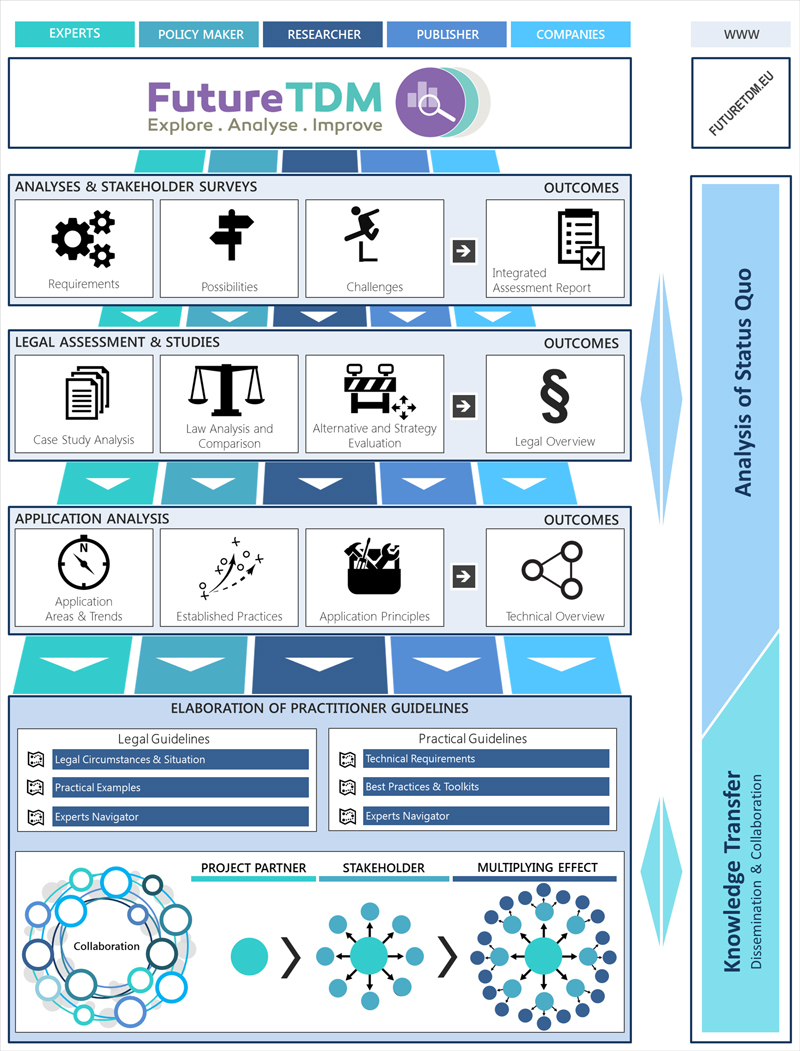

Overall Concept

The partners in the FutureTDM consortium share the ambition behind the EC’s call to develop policy and legal frameworks to reduce the barriers of TDM uptake and with it, promote the awareness of TDM opportunities across Europe. As a result, the consortium offers a concept that not only focuses on the required identification, assessment and analysis of current TDM obstacles, but also creates a practitioner-driven emphasis through engagement workshops and discussions. The consortium recognises that this topic is closely linked with the EINFRA-1 call Managing, preserving and computing with big research data, and thus will ensure strong connections with the EINFRA partners to guarantee a holistic approach to knocking down the barriers that are inhibiting TDM. An outcome of the FutureTDM project will include, guidelines that offer informed recommendations to practitioners from various disciplines, and propose solutions to overcome legal and policy barriers impeding TDM opportunities. Additionally, the project will create an online Collaborative Knowledge Base and Open Information Hub that will facilitate data-driven innovation through creative knowledge exchange and repositories of tools to address the gap in TDM skills across different areas.

An evaluation of the current state of TDM quickly reveals that there are several potential challenges to overcome if Europe is to address the gap in competitiveness in this area. Consortium members, LIBER and the British Library have already been involved in timely and insightful preliminary stakeholder dialogue. In September 2013, LIBER organised a workshop which brought stakeholders from science, policy, publishing, innovation, education and industry together in order to identify the issues blocking the potential of TDM. These issues ranged from the lack of legal certainty, the restrictiveness and lack of scalability of licences provided by publishers, a gap in skills, and lack of infrastructure. The following section identifies some key issues as well as the anticipated methodologies in the FutureTDM project to address these challenges.

Awareness

The current state of low demand to mine content from researchers is due to lack of awareness as well as the prohibitive amount of effort that is consumed by negotiating its legalities. It will become increasingly necessary for researchers to employ text and data mining to ensure the quality and accuracy of their research. Awareness raising amongst researchers about the potential and benefits of TDM as well as the related IP issues needs to occur. There is also some confusion in relation to the use of personal data. Consequently, there needs to be clear, understandable guidance for researchers and industry practitioners on how to deploy text and data mining ethically, responsibly, and sustainably.

© Sergey Nivens/Shutterstock.com/129303860

© everything possible/Shutterstock.com/134150393

Skills, Tools and Resources

In Europe, TDM is not prevalent across all disciplines despite that fact that it can help researchers to cope with the tripling rate of growth of scientific output. Therefore there is a gap in the basic skills (technical and otherwise) necessary in order to mine content for different areas of research. Furthermore, a similar argument can be made for the availability of tools for content mining. Libraries, who are charged with facilitating access to content also face a skills gap as they come to terms with providing content in a way that is accessible for TDM, curating data, storing TDM outputs and providing training on how to use TDM tools and the legal and other policy related aspect of performing TDM. As such, there needs to be modern coordination and support actions that provide equal access to tools and information to all current and future practitioners to boost TDM productivity.

Copyright

TDM activities may infringe copyright and/or the database right, if done without the rights owner’s prior authorisation. The fact that the research exception in the Database and Information Society Directives has not been implemented in all Member States creates uncertainty within the European scientific community. This is likely to bring about negative repercussions concerning the capacity of researchers to engage in TDM activities on a cross-border basis. Different options should be explored to allow, within the limits of the three-step-test, TDM activities to take place for research purposes irrespective of the category of works involved or of the commercial nature of the research activities.

Even if a statutory exception on copyright and database right is introduced, it will not necessarily guarantee access to minable content: contractual or technological restrictions may still prevent access to and reuse of content, including content that is not or no longer protected by IP rights. Indeed, access is one of the primary obstacles to TDM activities, since private actors are in no way obligated to open up and share the data they own with third parties. One of the biggest challenges facing TDM is therefore to find a balance of interests between owners of vast amounts of information and the research community.

© Feng Yu/Shutterstock.com/196309454

© Maksim Kabakou/Shutterstock.com/182554391

Licensing

One of the outcomes from Licences for Europe was a joint statement by STM publishers committing to providing licence solutions that would permit TDM. However, is this a viable solution to facilitate TDM? Even if the terms of these licences were to meet the needs of researchers wishing to perform TDM e.g. by permitting automated crawling of content and long-term deposit of copies in a secure repository, this would not solve the problems researchers in Europe face in relation to mining the open Web. From the library perspective, the negotiation of licences seems a time consuming and unscalable solution as it would involve negotiating with thousands of publishers on an individual basis and assumes that all publishers will agree to the same terms. The proliferation of licensing models and their inhibition of fostering open access principles is a critical issue that will be addressed by the FutureTDM consortium.

Open Access

The European Commission has made open access a general principle of Horizon2020 in order to boost innovation capacity. ‘Open access’ publications make scholarly literature freely available on the internet, so that it can be read, downloaded, copied, distributed, printed, searched, text mined, or used for any other lawful purpose, without financial, legal or technical barriers, subject to proper attribution of authorship. Open access improves the pace, efficiency and efficacy of research. It heightens the visibility of authors and the potential impact of their work. It removes geographical and structural barriers that hinder the free circulation of knowledge. Thereby contributing to increased collaboration, and ultimately strengthening scientific excellence and societal progress. It would seem therefore that open access is a major factor in increasing the uptake of TDM. Yet, it seems that the potential of open access as a means to facilitate data driven-innovation may be undermined by lack of interoperability between licences and the proliferation of licences which prohibit the creation of derivatives.

© Nomad_Soul/Shutterstock.com/116115739